WEEKLY HIGHLIGHTS FOR 1 OCTOBER 2004:

GRAVITY PROBE B MISSION UPDATE

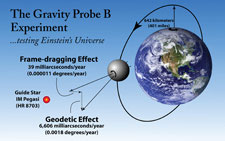

On Day 164 of the mission, the spacecraft is in good health, flying drag-free

around gyro #1. All four gyros are digitally suspended, and their SQUID readouts

are collecting relativity data during the portion of each orbit when the science

telescope is locked onto the guide star, IM Pegasi. The spacecraft’s

roll rate remains at 0.7742 rpm (one revolution every 77.5 seconds). The Dewar

temperature is nominal (1.82 Kelvin), and the flow of helium, venting from

the Dewar through the micro thrusters is within expected limits.

At this time of year in North America, at around 8:30 PM Pacific Daylight

Time, the constellation Pegasus, in which the guide star IM Pegasi resides,

is clearly visible above the Eastern horizon. With a magnitude ranging

from 5.6 – 5.85, IM Pegasi is too dim to see with the naked eye, but

in a good viewing location, it should be visible with binoculars.

In last week’s update, we reported that at 8:30 PM local time on Thursday,

23 September 2004, gyro #3—which was then serving as the drag-free gyro—suddenly

transitioned to analog backup suspension mode, automatically triggering a safemode

that stopped the mission timeline. The GP-B operations and engineering teams

quickly developed a recovery plan, and by the following afternoon, the spacecraft

was back in science mode, with gyro #1 performing the drag free operation.

The effect of this event on the science experiment was insignificant. The most

likely cause of this event was a data spike in the Gyro Suspension System (GSS)

position sensor for gyro #3. Gyro #3 was returned to digital suspension as

part of the recovery plan, and it has remained digitally suspended, with no

further problems, since that time. However, we are continuing to monitor its

performance and investigate the root cause. Thus, for the foreseeable future,

the spacecraft will continue to fly drag-free around gyro #1.

Also last week, we reported that the team had performed a heat pulse test

on the spacecraft Dewar in order to determine the mass of liquid helium remaining

inside, which determines the remaining lifetime of the mission. The heat pulse

test works in the following way: The amount of heat that it takes to warm an

object by a specified amount depends on the type of material, its temperature,

and its mass. Thus, if the "specific heat" (the amount of heat needed

to warm a kilogram of material by one degree kelvin) is known, it is a simple

matter to measure the mass by applying a known amount of heat (usually with

an electric heater) and measuring the resultant temperature rise. In the case

of the GP-B Dewar, the situation is simplified by the fact that heat distributes

itself virtually instantaneously throughout superfluid helium. The amount of

heat used in the test must be large enough to cause a measurable temperature

change (approximately 10 millikelvin) but not so large as to appreciably shorten

the mission lifetime. The heat pulse test yielded a remaining superfluid helium

mass of 216 kg, which translates into a remaining mission lifetime of 9.9 months.

This means that the science (data collection) phase of the mission will continue

for a little over 8 more months, and then we will spend the final month re-calibrating

the science instrument.

Finally, this past Tuesday, 28 September 2004, we observed a slight increase in the helium required by the micro thrusters to maintain drag-free flight around gyro #1. To be conservative, we decided to turn off drag-free mode and evaluate the situation. Over a period of 4-6 hours, the oscillations that were causing the ATC to require excess helium died out and have not returned. After some analysis and discussion, we have determined these oscillations were caused by a sympathetic resonance between the ATC drag-free control efforts and a sloshing wave on the surface of the now reduced superfluid helium in the Dewar. This situation is somewhat analogous to placing a vibrating tuning fork on the body of a guitar, which then causes guitar strings tuned to harmonics of the same frequency to start vibrating. This is a transient situation, and the team has adjusted the ATC drag-free suspension parameters to de-tune this harmonic coupling. We have since returned the spacecraft to drag-free operation around gyro #1, and it is performing nominally.

Images & photo: The diagrams of the GP-B experimental procedure and the cutaway drawing of the Dewar are from the GP-B Image Archives here at Stanford. The sky chart image, showing the constellation Pegasus and guide star, IM Pegasi in the October 1st mid-evening sky, as viewed from Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, was generated by the Voyager III Sky Simulator from Carina Software. The photo of the Dewar was taken by photographer Russ Underwood of Lockeed Martin Missiles & Space Company. Click on the thumbnails to view these images at full size.

Please Note: We will continue updating these highlights and sending out the GP-B email update on a weekly basis—at least through the first few weeks of the Science Phase of the mission. As mission operations become more routine, we may reduce the frequency of these updates to biweekly. However, from time to time, we intend to post special reports and special updates, as warranted by mission events.

SWISS AMATEUR ASTRONOMER PHOTOGRAPHS GP-B GP-B SPACECRAFT IN ORBIT WITH GUIDE STAR IM PEGASI

To the right, is a thumbnail of a photograph of the GP-B spacecraft in orbit, along with the guide star, IM Pegasi. (Click on the thumbnail to view the photo at full size.) The photo was taken and emailed to us by Stefano Sposetti, a Swiss physics teacher and amateur astronomer. Stefano used a 40cm newtonian telescope, with a CCD camera and 20mm wide field lens attached to make this photo. He then sent us the two versions shown — the normal (black sky) version on the right, and an inverse version in which the constellation, Pegasus, the guide star IM Pegasi, and the path of the GP-B spacecraft are highlighted for easy identification on the left.

We are grateful to Stefano for sending us this wonderful photo. You can view other astronomical photos that he has taken on his Web page: http://aida.astronomie.info/sposetti. Following is Stefano's description of his photo:

In this picture one can see the quite dim GP-B satellite traveling from North (up) to South (down) direction. The bold line in the right part of the left image represents the satellite trail just before entering the earth shadow. (Every satellite becomes visible because it reflects the sunlight). The connecting lines show the constellation Pegasus. The small circle around the star is IM Pegasi, the guide star used by the spacecraft's telescope in his experiment! GP-B is a circumpolar satellite following a free fall trajectory about 640km above the earth surface. From my location the satellite passed that night at a maximum elevation of 87degrees, thus not exactly overhead. The brightness of the satellite was between 3mag and 4mag. The Moon, about in the last quarter phase, illuminated the sky and was a drawback for having a good signal/noise ratio of the satellite trace. I took this 60-seconds black and white CCD picture with a 20mm,f/2.8 lens on august 6 centered at 01:19:00 UT. North is up, East is left.

More links on recent topics

- Track the satellite in the sky

- Photo, video & and news links

- Build a paper model of the GP-B Spacecraft

- Following the mission online

- Our mailing list - receive the weekly highlights via email

- The GP-B Launch Companion in Adobe Acrobat PDF format. Please note: this file is 1.6 MB, so it may take awhile to download if you have a slow Internet connection.

Previous Highlight

Index of Highlights