WEEKLY UPDATE FOR 6 MAY 2005:

GRAVITY PROBE B MISSION STATUS AT A GLANCE

| Item | Current Status |

| Mission Elapsed Time | 381 days (54 weeks/12.49 months) |

| Science Data Collection | 252 days (36 weeks/8.26 months) |

| Current Orbit # | 5,627 as of 5:00 PM PST |

| Spacecraft General Health | Good |

| Roll Rate | Normal at 0.7742 rpm (77.5 seconds per revolution) |

| Gyro Suspension System (GSS) | All 4 gyros digitally suspended in science mode |

| Dewar Temperature | 1.82 kelvin, holding steady |

| Global Positioning System (GPS) lock | Greater than 98.7% |

| Attitude & Translation Control (ATC) | X-axis attitude error: 178.8 marcs rms |

| Command & Data Handling (CDH) | B-side (backup) computer in control Multi-bit errors (MBE): 1 Single-bit errors (SBE): 9 (daily average) |

| Telescope Readout (TRE) | Nominal |

| SQUID Readouts (SRE) | Nominal |

| Gyro #1 rotor potential | -3.0 mV |

| Gyro #2 rotor potential | -3.8 mV |

| Gyro #4 rotor potential | -4.0 mV |

| Gyro #3 Drag-free Status | Backup Drag-free mode (normal) |

MISSION DIRECTOR'S SUMMARY

As of Mission Day 381, the Gravity Probe B vehicle and payload are in good health. All four gyros are digitally suspended in science mode. The spacecraft is flying drag-free around Gyro #3.

Further analysis of the results of the heat pulse test run on Tuesday, 26 April 2005, to determine the amount of liquid helium remaining in the Dewar, confirms the preliminary prediction that the helium in the Dewar will be depleted in late August or early September. Based on these results, the GP-B mission operations team is planning to complete readout calibrations, some of which can be done while we are still collecting science data, by the beginning of August. Gyro torque calibrations, which cannot be done during the science phase of the mission because they involve placing small torques (forces) on the gyro rotors, will commence early in August and continue until the helium runs out.

Our telescope pointing and guide star capture times continue to be excellent, thanks to recent fine-tuning of the spacecraft's Attitude and Translation Control system (ATC) parameters. We have also determined that we can reduce some noise in the SQUID Readout Electronics system (SRE) by turning off the Experiment Control Unit. However, we will now periodically power on the ECU for about 6 hours in order to obtain certain readouts that require information from the ECU.

Finally, a memory location in the B-side (backup) flight computer that is now controlling the spacecraft sustained a multi-bit error (MBE) last Saturday, 30 April 2005. The memory location affected is not currently being used. Following new procedures developed a few weeks ago, when we were experiencing an increased level of MBEs, our computer operations team quickly uploaded a patch to correct the contents of the affected memory location.

Also this past week, the GP-B Anomaly Review Board met to determine whether or not to change the pre-programmed safemode trigger and response to MBEs detected in the main flight computer. After a lengthy discussion, it was decided to change the safemode trigger condition from from 3 to 9 MBEs and the response actions from simply stopping the timeline (halting execution of the command set currently loaded into the computer) to automatically rebooting the computer. These changes ensure that if the error occurs in a memory location that increments the error counter at 10 Hz, the computer will automatically reboot immediately, rather than possibly freezing up and waiting for up to 8 hours for an "aliveness" test to trigger a reboot.

Also this past week, the GP-B Anomaly Review Board met to determine whether or not to change the pre-programmed safemode trigger and response to MBEs detected in the main flight computer. After a lengthy discussion, it was decided to change the safemode trigger condition from from 3 to 9 MBEs and the response actions from simply stopping the timeline (halting execution of the command set currently loaded into the computer) to automatically rebooting the computer. These changes ensure that if the error occurs in a memory location that increments the error counter at 10 Hz, the computer will automatically reboot immediately, rather than possibly freezing up and waiting for up to 8 hours for an "aliveness" test to trigger a reboot.

MISSION NEWS—WHITHER THE TELESCOPE DITHER?

Our Mission Director's summary last week mentioned turning off the telescope dither motion for a day in order to determine whether it is contributing in any way to experimental noise. This statement raises the obvious question, “What is the telescope “dither motion,” and what is its purpose?”

Webster's Dictionary defines the word dither as: “to shiver or tremble; to act nervously or indecisively-to vacillate.” When used in reference to technology, dither generally refers to the seemingly paradoxical concept of intentionally adding noise to a system in order to reduce its noise. A Web article posted by an audio engineer (Google Search: dither) states that this concept of dither dates back to the 1940's when British naval airmen discovered that the cogs and gears in the mechanical navigation systems of their airplanes would chatter and stick on the ground. However, once the planes were airborne, vibrations of the planes' engines had a lubricating effect on these mechanical navigation systems, smoothing out their operation. This discovery led the British Navy to install small motors in these mechanical navigation systems to intentionally vibrate the cogs and gears, thus improving their performance on the ground. Today, a random dithering technique is used to produce more natural sounding digital audio and another form of visual dithering enables thousands of color shades, used on Internet Web sites, to be derived from a limited basic palette of 256 colors.

With respect to the GP-B spacecraft, the dither refers to an oscillating movement of the science telescope that is activated whenever the telescope is locked onto the guide star. This intentional telescope movement produces a calibration signal that enables us to relate the signals generated by the telescope photon detectors to the signals generated by the SQUID magnetometer readouts of the gyro spin axis positions.

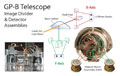

As described in our update of 5 November 2004, the sole purpose of the GP-B science telescope is to keep the spacecraft pointed directly at the guide star during the “guide-star-valid” portion of each orbit--that is, the portion of each orbit when spacecraft is “in front of” the Earth relative to the guide star and the guide star is visible to the telescope. This provides a reference orientation against which the spin axis drift of the science gyros can be measured. The telescope accomplishes this task by using lenses, mirrors, and a half-silvered mirror to focus and split the incoming light beam from the guide star into an X-axis beam and a Y-axis beam. Each of these beams is then divided in half by a knife-edged “roof” prism, and the two halves of each beam are subsequently focused onto a pair of photon detectors. When the detector values of both halves of the X-axis beam are equal, we know that the telescope is centered in the X direction, and likewise, when the detector values of both halves of the Y-axis beam are equal, the telescope is centered in the Y-axis direction. (The telescope actually contains two sets of photon detectors, a primary set and a backup set for both axes.)

As described in our update of 5 November 2004, the sole purpose of the GP-B science telescope is to keep the spacecraft pointed directly at the guide star during the “guide-star-valid” portion of each orbit--that is, the portion of each orbit when spacecraft is “in front of” the Earth relative to the guide star and the guide star is visible to the telescope. This provides a reference orientation against which the spin axis drift of the science gyros can be measured. The telescope accomplishes this task by using lenses, mirrors, and a half-silvered mirror to focus and split the incoming light beam from the guide star into an X-axis beam and a Y-axis beam. Each of these beams is then divided in half by a knife-edged “roof” prism, and the two halves of each beam are subsequently focused onto a pair of photon detectors. When the detector values of both halves of the X-axis beam are equal, we know that the telescope is centered in the X direction, and likewise, when the detector values of both halves of the Y-axis beam are equal, the telescope is centered in the Y-axis direction. (The telescope actually contains two sets of photon detectors, a primary set and a backup set for both axes.)

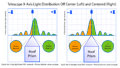

The telescope detector signals are converted from analog to digital values by the Telescope Readout Electronics (TRE) box, and these digital values are normalized (mapped) onto a range of -1 to +1. In this normalized range, a value of 0 means that the telescope is centered for the given axis, whereas a value of +1 indicates that all of the light is falling on one of the detectors and a value of -1 indicates that all of the light is falling on the other detector. In actuality, the light beam for each axis is distributed in a bell-shaped curve along this scale. When the telescope is centered, the peak of the bell curve is located over the 0 point, indicating that half the light is falling on each detector. If the telescope moves off center, the entire curve shifts towards the +1 or -1 direction. You can think of this as a teeter totter of light values, with the 0 value indicating that the light is balanced. (See the drawings to the right.)

The telescope detector signals are converted from analog to digital values by the Telescope Readout Electronics (TRE) box, and these digital values are normalized (mapped) onto a range of -1 to +1. In this normalized range, a value of 0 means that the telescope is centered for the given axis, whereas a value of +1 indicates that all of the light is falling on one of the detectors and a value of -1 indicates that all of the light is falling on the other detector. In actuality, the light beam for each axis is distributed in a bell-shaped curve along this scale. When the telescope is centered, the peak of the bell curve is located over the 0 point, indicating that half the light is falling on each detector. If the telescope moves off center, the entire curve shifts towards the +1 or -1 direction. You can think of this as a teeter totter of light values, with the 0 value indicating that the light is balanced. (See the drawings to the right.)

A telescope scale factor translates the values on this normalized scale into a positive or negative angular displacement from the center or 0 point, measured in milliarcseconds (1/3,600,000 or 0.00000028 degrees). Likewise, a gyro scale factor translates converted digital voltage signals representing the X-axis and Y-axis orientations of the four science gyros into angular displacements, also measured in milliarcseconds. We now have both the telescope and gyro scale factors defined in comparable units of angular displacement. The telescope dither motion is then used to correlate these two sets of X-axis and Y-axis scale factors with each other.

The telescope dither causes the telescope (and the entire spacecraft) to oscillate back and forth in both the X and Y directions around the center of the guide star by a known amount. Because this motion moves the entire spacecraft, including the gyro housings that contain the SQUID pickup loops, the SQUIDs detect this oscillation as a spirograph-like (multi-pointed star pattern) that defines a small circle around the center of the guide star. This known dither pattern enables us to directly correlate the gyro spin axis orientation with the telescope orientation. The result is a pair of X-axis and Y-axis scale factors that are calculated for the guide-star-valid period of each orbit. At the end of the data collection period this July, we will have stored between 6,500 and 7,000 sets of these scale factors, representing the motion of the gyro spin axes for the entire experiment. (The drawing to the right depicts the telescope dither pattern around the guide star, IM Pegasi.)

The telescope dither causes the telescope (and the entire spacecraft) to oscillate back and forth in both the X and Y directions around the center of the guide star by a known amount. Because this motion moves the entire spacecraft, including the gyro housings that contain the SQUID pickup loops, the SQUIDs detect this oscillation as a spirograph-like (multi-pointed star pattern) that defines a small circle around the center of the guide star. This known dither pattern enables us to directly correlate the gyro spin axis orientation with the telescope orientation. The result is a pair of X-axis and Y-axis scale factors that are calculated for the guide-star-valid period of each orbit. At the end of the data collection period this July, we will have stored between 6,500 and 7,000 sets of these scale factors, representing the motion of the gyro spin axes for the entire experiment. (The drawing to the right depicts the telescope dither pattern around the guide star, IM Pegasi.)

The reason we turned off the dither motion for a day last week was to determine what effect, if any, the dither itself was contributing our telescope pointing noise and accuracy. The results of this test indicate that the navigational rate gyros, which are used to maintain the attitude of the spacecraft and telescope during guide-star-invalid periods (when the spacecraft is behind the Earth), are the dominant source of noise in the ATC system, whereas the science gyro signals are stronger than the noise in the SQUID Readout Electronics (SRE) system.

UPDATED NASA/GP-B FACT SHEET AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOADING

We recently updated our NASA Factsheet on the GP-B mission and experiment. You'll now find this 6-page document (Adobe Acrobat PDF format) listed as the last navigation link under "What is GP-B" in the upper left corner of this Web page. You can also click here to download a copy.

THE EINSTEIN EXHIBITION AT THE SKIRBALL CULTURAL CENTER IN LOS ANGELES

If you're going to be in Los Angeles anytime before 30 May 2005, and if you’re interested in Einstein’s life and work, the Einstein Exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center (just north of the Getty Museum on Interstate 405) is the most comprehensive presentation ever mounted on the life and theories of Albert Einstein (1879-1955). It explores his legacy not only as a scientific genius who re-configured our concepts of space and time, but also as a complex man engaged in the social and political issues of his era. It examines the phenomenon of his fame and his enduring status as a global icon whose likeness has become virtually synonymous with genius.

If you're going to be in Los Angeles anytime before 30 May 2005, and if you’re interested in Einstein’s life and work, the Einstein Exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center (just north of the Getty Museum on Interstate 405) is the most comprehensive presentation ever mounted on the life and theories of Albert Einstein (1879-1955). It explores his legacy not only as a scientific genius who re-configured our concepts of space and time, but also as a complex man engaged in the social and political issues of his era. It examines the phenomenon of his fame and his enduring status as a global icon whose likeness has become virtually synonymous with genius.

In this exhibit, you can examine Einstein's report card, inspect his FBI file, and enjoy his family photographs, love letters, and diary entries. Exhibition highlights include scientific manuscripts and original correspondence—including original handwritten pages from the 1912 manuscripts of the special theory of relativity and his 1939 letter to President Roosevelt about nuclear power—and a wealth of other documents from the Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

In addition to these displays of Einstein memorabilia, the exhibit also features a number of interactive components that help provide an understanding of Einstein's revolutionary theories. Furthermore, several “explainers,” identified by their red aprons, are on hand to discuss various aspects of the exhibit and to explain and demonstrate difficult concepts, such as time dilation and warped spacetime. At the end of the exhibit, you’ll find one of GP-B’s gyro rotors on display.

The Einstein exhibition was jointly organized by the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the Skirball Cultural Center. It was designed by the AMNH under the supervision of Dr. Michael Shara, curator of the exhibit and chairman of the museum’s Astrophysics Department. It opened in November 2002 at the AMNH in New York and then traveled to Chicago and Boston, spending about 8 months in each location. It will remain at its final U.S. stop at the Skirball Center in Los Angeles through 29 May 2005, after which time it will move permanently to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Information about the Einstein exhibition is available on the Skirball Center Web site. If you can’t make it to Los Angeles, you can visit the AMNH’s virtual Einstein exhibit on the Web.

Drawings & Photos: The Photoshop composite of the GP-B spacecraft in orbit and all of the drawings depicting the telescope normalized pointing and dither were created by GP-B Public Affairs Coordinator, Bob Kahn. The photos of the Dewar, ECU electronics box, and the Anomaly Review Board are from the GP-B Photo & Graphics Archive here at Stanford. Finally, the photos from the Einstein Exhibit are courtesy of the Skirball Cultural Center. Click on the thumbnails to view these images at full size.

MORE LINKS ON RECENT TOPICS

- Track the satellite in the sky

- Photo, video & and news links

- Build a paper model of the GP-B Spacecraft

- Following the mission online

- Our mailing list - receive the weekly highlights via email

- The GP-B Launch Companion in Adobe Acrobat PDF format. Please note: this file is 1.6 MB, so it may take awhile to download if you have a slow Internet connection.

Previous Highlight

Index of Highlights