Frequently Asked Questions

Photos, Press, Mailing & General Information:

- How can I follow the GP-B mission besides this web site?

- Do you have a project mailing list to subscribe to bulletins?

- How can I track the GP-B satellite in the night sky?

- Do you have pictures and video, or newsclips on the launch?

- Is there a DVD about this project that I can order?

- I am doing a feature about GP-B - how can you help me?

The Mission - History and the Present:

- How did you choose the guide star? What is its significance

- Where is GP-B controlled?

- When and where was GP-B launched?

- Why did Gravity Probe B have a one-second launch window?

- Did the Indonesian earthquake and tsunami have an effect on GP-B? Did you detect it in your measurements?

- What is "wrapping the bubble" and how did you do it? How was the spacecraft's mass precisely centered?

- What is digital and analog suspension? What is the difference?

- How does your data get to the ground and what do you do with it?

General Program Questions:

- What does "GP-B" actually stand for?

- Which of Einstein's theories is the project trying to test?

- Is the project part of Stanford University?

- Who actually built the satellite and where?

- Is GP-B funded by the National Science Foundation, NASA or other national agencies, or is it privately funded? Where does the money come from?

- What happened to Gravity Probe "A"?

- What is the purpose of Gravity Probe B? Is it worth doing?

Questions about Relativity:

- What is the General Theory of Relativity?

- How does GP-B plan to test the General Theory of Relativity?

- What is space-time?

- What is the Equivalence Principle?

Pictures, Mailing & General Information:

- How can I follow the GP-B mission besides this web site?

- Do you have a project mailing list to subscribe to bulletins?

Sure - if you are interested in automatically receiving the weekly highlights and other important GP-B mission information by email, you can subscribe to our Gravity Probe B update email list by sending an email message to "majordomo@lists.Stanford.edu" with the command "subscribe gpb-update" in the body of the message (not in the Subject line). You can unsubscribe from this mailing list at any time by sending an email message to the same address with the command, "unsubscribe gpb-update" in the body of the message.

Please Note: During the Initialization & Orbit Checkout (IOC) Phase of the GP-B mission, we update the Web site and send out an email update once a week (usually on Thursday or Friday) to keep you apprised of our progress. From time to time, we may post and email extra updates, as warranted by mission events.

- How can I track the GP-B satellite across the night sky?

- Do you have pictures and video, or news clips on the launch?

- Is there a DVD about this project that I can order?

- I am doing a feature about GP-B - how can you help me?

In addition to this Web site, here are some other Web sites that have

information, photos, and video of the GP-B launch and mission.

ELV

Missions Virtual Launch Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center Web site has information and several

streaming video clips covering the GP-B mission. (You can view these video

clips free of charge, but you will need to have either

the Real Media Player or Windows Media Player installed on your computer

to view them.)

Gravity Probe

B.com Web page

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center has a number of great photos from

the GP-B launch, including photos of the spacecraft separation, as well as

other information about Gravity Probe B.

Science @ NASA

Web site hosted by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center that posts several

stories each month about scientific research projects in which NASA is involved.

This site currently features two general interest stories

about Gravity Probe B: In

search of Gravitomagnetism and A

Pocket of Near Perfection. (In addition to the Web versions, these stories

are also available in both plain text and streaming audio formats.)

More information about launch photos is below

.

Find the Gravity Probe B satellite in the sky at NASA's satellite tracking web site. See where GP-B is with respect to the terminator (the day-night boundary on the Earth's surface), or just enter your zip code to see if GP-B might be over your neighborhood. The best time to look for it is usually at dusk.

Also, you can track the GP-B spacecraft on your Palm OS or Pocket PC Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), using either PocketSat or PocketSat+ from Big Fat Tail Productions. Both products are PDA Shareware, so you can try them out for free. If you decide to use them, Big Fat Tail asks that you pay a nominal shareware fee.

Yes we do. Please have a look at our "news clips" section found under the News/Media section of our site.

Yes there is. Norbert Bartel, Professor of Astrophysics and Space Sciences at York University in Toronto, Canada, has produced and directed a 26-minute documentary movie about the Gravity Probe B experiment entitled, Testing Einstein's Universe. This movie, along with 80 minutes of additional video about relativity, physics, and astronomy is available on a DVD, which you can purchase from the Website: http://www.astronomyfilms.com/

We have high-resolution graphics available at our High resolution photo gallery. These graphics have captions and credits. Most of these are free of charge - we ask only for proper credit to the photographer. If you don't see what you're looking for, please write to our Public Relations person, Bob Kahn, or to the webmaster for assistance. Bob can answer any questions you might have about how our mission works and help with photos and video.

The Mission - History and the Present:

- How did you choose the guide star? What is its significance?

- Where is GP-B controlled?

- When and where was GP-B launched?

- Why did Gravity Probe B have a one-second launch window?

- Did the Indonesian earthquake and tsunami have an effect on GP-B? Did you detect it in your measurements?

- What is "wrapping the bubble" and how did you do it? How was the spacecraft's mass precisely centered?

- What is digital and analog suspension? What is the difference?

The more important measurement conducted by the science instrument is that of the angle between the spin axis of our gyroscopes and the fixed reference line provided by our guide star (via our on-board telescope). Effectively, we determine the rate of change of the gyro spin directions in comparison to the direction of one particular star. By means of our specialized guiding telescope, the spacecraft is kept pointing at this "guide star" for almost the entire mission. But is this guide star an adequate reference point, fixed on the sky with respect to the galaxies lying behind it? The answer is "No!" Like everything else in the universe, stars move, and are not fixed points on the sky. Our guide star (like all stars) is free to move slowly across the sky, and this motion cannot be ignored in the GP-B test of general relativity. In fact, the European space mission Hipparcos has shown that each year the chosen guide star moves across the sky about 35 milliarcseconds, almost as much as the entire relativistic gravitomagnetic effect in one year. Moreover, the uncertainty of this value is larger than the intended accuracy of the of the GP-B relativity tests. Some other method was needed to measure the motion of the guide star.

The solution to this problem was to choose a star that emits not only light that can be observed with the telescope of the GP-B spacecraft, but also microwave radio noise that can be recorded by large astronomical and deep space communication radio antennas on the ground. The chosen star is IM Pegasi--in Latin "Pegasi" means "of or in Pegasus," which is a constellation of stars easily seen high over head on autumn evenings throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. The designation "IM" is just a pair of letters chosen more or less sequentially to identify certain stars. This star IM Pegasi is barely bright enough to see with the naked eye under very dark and clear skies, but when observed in the microwave range, this star is often among the brightest in the sky. The microwave noise coming from this star makes it possible to use the methods of very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI) to measure the position of the star in comparison to several quasars that lie nearby to the star on the sky. Quasars are galaxies with a quasi-stellar (i.e., nearly unresolved) appearance found in the distant universe millions of times farther away from the Earth than the stars visible to the naked eye. The wonderful thing about these quasars is that even though they are far enough away to be ideal reference points for the relativity tests, they emit so much microwave radio energy that they appear to radio antennas to be among the brightest objects in the sky, in many cases even brighter than the guide star.

To measure the motion on the sky of this particular star, since 1997 the GP-B program has obtained VLBI observations of this star and at least two quasars behind it about four times per year. Data is recorded with the VLA and VLBA radio antenna arrays of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), the 70 meter diameter dishes of NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN) and the 100 meter diameter dish of the Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie (MPIfR) in sessions lasting up to 18 hours. The data from all the antennas are initially combined and processed by NRAO in Socorro, NM, before being sent to York University, in Toronto, Canada, and to the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in Cambridge, MA, for further analysis. The use of so many telescopes increases both the accuracy of the measurements and their ability to detect the the sometimes weak radio emission from IM Pegasi. The results of this analysis are a series of maps and positions from which the motions of IM Pegasi can be estimated. By the end of the GP-B mission, these observations should determine the mean (or so-called "proper") motion of IM Pegasi against the distant galaxies to an accuracy of about 0.1 milliarcseconds per year. This accuracy is comparable to the intended accuracy of the measurement of the mean rate of change of the gyro spin directions with respect to IM Pegasi. Combined together, these measurements will determine the mean rate of change of the gyro spin directions with respect to the distant universe. Together they will test, with much greater accuracy than ever before, the two predictions of general relativity for the behavior of gyroscopes near a massive body, and thus reveal something about the nature of space-time itself.

Some readers have asked for alternative naming conventions for our guide star, as it appears listed in different catalogs. These names can include: IM Peg, HR 8703, HD 216489, SAO 108231, BD +16 4831, FK5: 3829

Pages 18-20 of the Gravity Probe B Launch Companion contain information about the guide star and the science telescope. Furthermore, the ETH Institute of Astronomy in Zurich, Switzerland, is working with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics to provide detailed optical information about the GP-B guide star, IM Pegasi. You can find out about the ETH Institute's work in monitoring magnetic activity on IM Pegasi and the Doppler Imaging Technique used for this purpose on the ETH Institute of Astronomy GP-B Web page.

The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (Cambridge) and York University (Toronto) are studying the guide star to provide crucial measurements of its motion relative to far away quasars. These measurements are needed to relate the tiny changes in the gyroscopes' spin direction to the distant universe, so that general relativity can be tested. Learn more about these measurements by going to the IM Pegasi web site at York University.

The spacecraft is being controlled from the Gravity Probe B Mission Operations Center, located here at Stanford University. The Stanford-NASA/MSFC-Lockheed Martin operations team is continuing to perform superbly.

The Gravity Probe B space vehicle was launched on Tuesday, April 20, 2004, at 9:57:24 AM Pacific Daylight Time. The space vehicle was launched using a Delta II rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in South-Central California. Mission life is expected to be approximately 16 months.

The spacecraft needed to be launched exactly into an orbit plane aligned with the guide star. how close "exactly" actually needs to be is defined by the science team, but it turns out to be around +/- 0.04 degrees of longitude (in rough terms). Note the plane of the guide star (a plane defined by the center of the earth, the north pole, and the guide star) is fixed or "inertial" in space. This plane does notrotate with the earth.

We know the earth rotates completely around (360 degrees) in 24 hrs (86400 seconds), which means the earth turns through (360 deg/86400 sec) 0.004 deg/sec. This means that you, me, and the rocket on the ground are constantly rotating around at this rate. So, in theory, it takes the earth 10 seconds to turn through 0.04 degrees, which is our maximum, theoretical "window" on any given day.

So why was our launch window one second instead of ten seconds? The maximum accuracy of the Delta II rocket is only about +/- 0.03 degrees. This now only leaves about 2 seconds of margin in our maximum theoretical window. Build in a factor of safety here and there for other considerations, namely, whether the rocket is launched half a second early or late, and you're left with a one-second window. There are also some second- and third-order effects to consider, but they are outside the scope of this discussion.

We have received numerous inquiries regarding any possible relationship between GP-B's experimental measurements and the disastrous earthquake and ensuing tsunami in South Asia on December 26th. The short answer is that this event had no effect on the GP-B experimental data, nor did our gyroscopes detect it. For readers who are interested, more detailed information follows.

Richard Gross, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, California, has modeled the coseismic effect on the Earth's rotation of the December 26 earthquake in Indonesia by using the PREM model for the elastic properties of the Earth and the Harvard centroid-moment tensor solution for the source properties of the earthquake. The result of this modeling is:

Change in length of day: -2.676 microseconds (about one second in a millennium)

X-axis polar motion excitation: -0.670 milliarcseconds (approximately 2 centimeters or 0.8 inches)

Y-axis polar motion excitation: +0.475 milliarcseconds (approximately 1.5 centimeters or 0.6 inches)

Since the length of the day can only be measured to an accuracy of about 20 microseconds (20 millionths of a second), this model predicts that the change in the length-of-day caused by the earthquake is too small to be observed. And, since the location of the earthquake was near the equator, this model predicts that the change in polar motion excitation is also rather small, being about 0.82 milliarcsecond in amplitude. Such a small change in polar motion excitation will also be difficult to detect.

Nevertheless, at a science conference in Utah last week, Professor Ulrich Schreiber of the Munich Technical

University in Germany reported that his Earth-based, ultra-precise "G" ring laser gyroscope was able to detect

perturbations in the Earth's axis as a result of the Indonesian earthquake. This gyroscope--the largest of its kind

in the world--contains a giant glass ceramic disc, 4.25 meters in diameter, 25 centimeters thick and weighing 10

tons. It is located in a sealed and pressurized chamber, eight meters below the surface of the Earth, at the

Wettzell Fundamental Research Station in New Zealand. This instrument was specifically designed to be able to detect

changes in the Earth's rotation within a day. For more information on the "G" ring laser gyroscope, see a 1996

article on the Web site of the International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE) or download a PDF copy of a 2003

paper from the Wettzell Fundamental Research Station.

In contrast, the GP-B gyroscopes have not detected any measurable effect as a result of the Indonesian earthquake and tsunami. GP-B is measuring the curvature and twisting of space-time around the Earth, not the planet itself. Our spacecraft is in a circular orbit, 640 kilometers (400 miles) above the earth, always passing over the north and south poles, but varying in its longitudinal path with each orbit. The extremely small change in the earth's polar motion resulting from the Indonesian earthquake/tsunami is simply not significant enough to appear in our measurements. Also, any small change in the Earth’s polar motion will factor itself out, given the changing longitude of each orbit.

Our measurements do depend on knowing our spacecraft’s position relative to specific locations on Earth to a high precision, and for these measurements, we use the Global Positioning System (GPS). It is possible, though highly unlikely, that if a re-calibration in the GPS satellites is required, we may need to incorporate some compensating factors.

Gravity Probe B could conceivably register a change in Earth’s polar orbit, if the change were of immense proportions. For example, suppose the earth's spin axis were to change position by 3 degrees. This would significantly affect local space-time, and this change would be detectable by the science instruments on-board the spacecraft. However, such a change would require a cataclysmic event, ten million times larger than the Indonesian earthquake and tsunami—an event that would mean the end of Planet Earth, as we know it.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) maintains a Web page of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about the December 26th earthquake and tsunami.

All of us on the Gravity Probe B team are deeply saddened by human tragedy that has emerged in the wake of the tsunami. The importance of global relief efforts cannot be overstated.

Centering the spacecraft's mass is a careful process that took several "try

and see" adjustments over a period of about two weeks.  "Wrapping the bubble" is part of balancing the roll of the spacecraft.

During the week of June 25th, 2004, we engaged in two procedures designed

to bring the entire spacecraft into balance, rolling smoothly about its main

axis while the telescope focuses on the guide star. In the first procedure,

called “bubble wrap,” the spacecraft’s roll rate was increased

in incremental steps, from 0.3 rpm to 0.9 rpm.

The increased roll rate begins to rotate the liquid helium, effectively pushing

it outwards as it tries to move in a straight line with its intertia. The Dewar walls hold it in with a

centripetal force. This wraps the helium uniformly around the outer shell.

Distributing the liquid helium uniformly along the spacecraft’s roll axis helps

to ensure that the science telescope can remain locked on the guide star while the spacecraft is rolling.

"Wrapping the bubble" is part of balancing the roll of the spacecraft.

During the week of June 25th, 2004, we engaged in two procedures designed

to bring the entire spacecraft into balance, rolling smoothly about its main

axis while the telescope focuses on the guide star. In the first procedure,

called “bubble wrap,” the spacecraft’s roll rate was increased

in incremental steps, from 0.3 rpm to 0.9 rpm.

The increased roll rate begins to rotate the liquid helium, effectively pushing

it outwards as it tries to move in a straight line with its intertia. The Dewar walls hold it in with a

centripetal force. This wraps the helium uniformly around the outer shell.

Distributing the liquid helium uniformly along the spacecraft’s roll axis helps

to ensure that the science telescope can remain locked on the guide star while the spacecraft is rolling.

Some people might think this is centrifugal force. One might ask, what is the difference between centripetal and centrifugal force, anyway?

The words centripetal and centrifugal are in fact antonyms defined as follows:

centrifugal : tending to move away from a center.

centripetal : tending to move toward a center.

The second procedure was "mass trim". Mass trim uses weights mounted on long screw shafts attached in

strategic locations around the spacecraft frame. Small motors, under control of the spacecraft’s Attitude &

Translational Control system, can turn these screw shafts in either direction, causing the weights to move back

and forth by a specified amount. Thus, based on feedback from the GSS, the spacecraft’s center of mass can

be precisely centered, both forward to back, and side to side, around the

designated “drag-free” gyro.

The second procedure was "mass trim". Mass trim uses weights mounted on long screw shafts attached in

strategic locations around the spacecraft frame. Small motors, under control of the spacecraft’s Attitude &

Translational Control system, can turn these screw shafts in either direction, causing the weights to move back

and forth by a specified amount. Thus, based on feedback from the GSS, the spacecraft’s center of mass can

be precisely centered, both forward to back, and side to side, around the

designated “drag-free” gyro.

Digital and analog refer to two methods of controlling the position of spinning gyroscope rotors inside their housings. The Gyroscope Suspension System applies tiny, precise electromagnetic potential changes as needed inside each rotor housing. There are three electrodes on each housing half (six total per complete housing) that monitor and then control the electrostatic suspension of the GP-B gyros. You can learn more about the gyroscope hardware in our educational lithograph.

As of May 7th, all four gyros have been electrically suspended in analog mode, and gyros #1, #2 and #4 are now digitally suspended; we expect gyro #3 to transition from analog to digital suspension shortly.

General Program Questions:

- What does "GP-B" actually stand for?

- Which of Einstein's theories is the project trying to test?

- Is the project part of Stanford University?

- Who actually built the satellite and where?

- Is GP-B funded by the National Science Foundation, NASA or other national agencies, or is it privately funded? Where does the money come from?

- In March 1964, retroactive to November 1963, NASA began funding the feasibility of the mission and preliminary technology development. Low level funding continued through 1985.

- In 1982 NASA performed a study of the program which recommended amongst other things a significant up front technology investment to develop the experiment payload.

- After numerous discussions and negotiations, NASA in Fiscal Year 1985 initiated a program called STORE (Shuttle Test of the Relativity Experiment) to perform part of the experiment. NASA's intention at that time was to build the final flight instrument, do an experimental rehearsal with the instrument captive on Shuttle after which it would be returned to earth for refurbishing and joining with its own space vehicle. The full spacecraft then would be re-flown on Shuttle and launched from Shuttle as a free flyer, assuming shuttle launch into the required polar orbit from SLC-6 at Vandenberg Air Force Base.

- The plans for STORE were modified in consequence of the Challenger tragedy in 1986, the subsequent cutbacks in the number of shuttle missions, and the closure of the SLC-6. STORE was, however, continued as an instrument development program without a shuttle test.

- In 1993, following two independent studies of the Gravity Probe B spacecraft, NASA approved selection of one contractor (Lockheed Martin Missiles and Space) and the start of the full GP-B flight program.

- What happened to Gravity Probe "A"?

- The primary objective of the GP-A mission is to test a fundamental postulate of gravitation and relativity theories called the "Principle of Equivalence" to an accuracy of 200 parts per million by testing whether the principle holds for extended regions of space where the gravitational acceleration has considerably different values.

- A secondary objective is the demonstration of a hydrogen MASER clock in space.

- What is the purpose of Gravity Probe B? Is it worth doing? (Click Here for the answer)

"GP-B" stands for "Gravity Probe B".

The Gravity Probe B Relativity Experiment (GP-B) is a joint NASA/Stanford University orbiting astrophysics experiment to test two predictions of Einstein's theory of General Relativity: the geodetic and frame-dragging effects, the second of which has never been experimentally observed. The relativistic sensors for this experiment are four identical, ultra-precise mechanical, electrostatically-suspended vacuum gyroscopes (ESVG) carefully isolated from Newtonian torques. General relativity predicts that the spin axes of these gyroscopes will precess with respect to a distant inertial reference frame at a rate of 6.6 arc-seconds per year for the geodetic effect, and 42 milliarcseconds per year due to frame-dragging in the circular, polar orbit. To achieve the levels of measurement precision needed in this experiment, the orientation of the gyroscopes' spin axes must be aligned to within 10 arcsecond of the line-of-sight to a distant guide star, IM Pegasi (HR 8703).

Yes. Our administration is on campus and our science instrument was built in a Stanford laboratory - the W. W. Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory to be precise. Stanford was selected by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center as the prime contractor responsible for the entire Gravity Probe B Program. This includes the responsibilities of building the science instrument, of overseeing deliverable components (such as our Dewar and our space vehicle) from our contractor, Lockheed Martin Missiles and Space, and Mission Operations and Data Analysis. This is the first time NASA has allowed a university to completely manage the development and operation of a major scientific satellite.

Stanford is Prime Contractor to NASA Marshall Space Flight Center with a major subcontract to Lockheed Martin Missiles and Space. There have been in the vicinity of 500 subcontracts from Stanford and Lockheed for different individual subsystems, including, incidentally, a subcontract to the Harvard Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory for refined measurements of the proper motion of the GP-B guide star. Essentially, there were two main groups responsible for building the entire Gravity Probe B satellite: Stanford and Lockheed. Stanford University built the Science Instrument which consists of the gyroscopes and their systems, the quartz block, the SQUIDs and the telescope. Some of the electronics for collecting and sending the science data were also built at Stanford. Many of the electronic components for GP-B as well as the Dewar, Probe and Spacecraft were built nearby by Lockheed Martin Missiles and Space. The Ground Station, which receives all data from the satellite after launch, is located on the Stanford University campus.

The story of the funding of Gravity Probe B is a rather interesting one:

Gravity Probe A was a joint program of NASA-Marshall Space Flight Center and the Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institution. It was also the first test in space to explore the structure of space and time. It is known to many scientists as the "Red Shift Experiment" or the "Clock Experiment." The Gravity Probe A (GP-A) payload was launched on June 18, 1976 at 7:41 A.M. Eastern Daylight Time from the NASA-Wallops Flight Center in Virginia. Unlike Gravity Probe B, GP-A was only in space for one hour and 55 minutes in an elliptical flight trajectory over the Atlantic. It attained a maximum height of 6200 miles above the earth before impacting into the Atlantic Ocean. Why was GP-A in space for such a short time? No accidents on the launch pad - it was part of the design of the experiment (unlike Gravity Probe B, which will be in a polar orbit over the Pacific Northwest for nearly two years). To yield an accurate and inexpensive experiment, GP-A required a flight path with a large change in the gravitational potential to provide a large gravitational redshift, and it required a flight path that kept the flight Hydrogen MASER in contact with the ground Hydrogen MASER during data collection.

The official, formal Mission Objectives of Gravity Probe A are listed by NASA as the following:

For more information, read The basic scope of the Gravity Probe A experiment summarized from NASA News, 1976. Or read Gravitation Research Using Atomic Clocks in Space by Dr. R. F. C. Vessot, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Principal Investigator, Gravity Probe A.

In the GP-A mission, all payload systems appeared to have functioned properly, including the newly-developed hydrogen MASER, NASA officials reported. Successful tracking was maintained throughout the mission. NASA's Post Launch Mission Operation Report of GP-A dated February 14, 1977, states the following:

The Principal Investigator, Dr. R. F. C. Vessot began data reduction and has reported achieving 150 parts per million accuracy. The prelaunch accuracy objective of 200 parts per million from the data has thus been surpassed. Based on this report, the mission is adjudged as successful.

To learn more about Dr. Vessot's current research, have a look at The Hydrogen Maser Clock Project home page at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Questions about Relativity:

- What is the General Theory of Relativity?

- How does GP-B plan to test the General Theory of Relativity?

- What is space-time?

- What is the Equivalence Principle?

The short answer: According to Einstein the presence of a gravitational field alters the rules of geometry in space-time. The effect is to make it seem as it space-time is "curved."

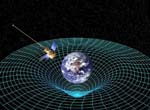

The explanation: Einstein realized that Newton's theory of gravitation (the classically accepted theory) did not account for events over extremely large distances. In particular, Newton's theory says that the gravitational force between two objects is proportional to the masses of the objects divided by the square of the distance between the objects. This means that two stars will have a gravitational force between them and will be attracted to each other. How strong the force is depends on how massive they each are and how much space is between them. This makes sense when the stars are not too far away from each other. But what if they were really far apart, say in different corners of the universe? And what if the mass of one of the objects suddenly changed, due perhaps to its experiencing an explosive supernova where it would convert some of its mass to energy? Newton's theory implies that the change in the gravitational force between the objects should change instantly. Einstein wondered how these immediate changes in force could be possible. The theory of Special Relativity states that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (Special Relativity theory has been verified in many experiments all over the world), so how could gravitational force changes be "transmitted" to the rest of the universe so quickly? This implied that perhaps space was not just some empty spot where things happened instantly, but rather that space itself, combined with time, must form some kind of fabric. The shape and form of this space-time fabric would govern the flow of signal transmission and the paths of the movement of light in a way similar to the way the lay of the land determines which way water flows during a rainstorm. This fabric would react to changes in mass and energy the way any fabric responds to changes in pressure and to movement. In fact, we say that mass-energy determines the shape of the fabric of space-time. A good way to imagine how a mass-energy (such as the Earth) affects its local area of space-time might be to imagine a stretched fishing net with a basketball in it. Where the net dips and twists is dependent on how the basketball moves and where it is placed. As soon as a mass-energy is introduced into an area, space-time is warped accordingly. Because space-time is warped, and light (and other electromagnetic signals such as radio waves) has to travel in space-time, its pathways follow the warp. Electromagnetic fields should also be affected by the curvature of space-time. We at Gravity Probe B are looking for predicted changes to the local electromagnetic field in accordance with the amount of warp, or curvature, created by the presence of the mass-energy of the Earth.

For more information on General Relativity, check out the PBS program NOVA Online "Einstein Revealed" web site.

The earth is a mass-energy. According to General Relativity, as a mass-energy, it should create a little dimple in the local space-time fabric. It is also theorized that the daily rotation of the earth causes a twisting of the local space-time fabric.

"This effect is known as frame dragging

and it should manifest itself as a force that pushes a gyroscope's axis

out of alignment as it orbits the Earth. [GP-B will be using four small,

incredibly precise gyroscopes as its main tool for detection of relativistic

effects on the local space-time fabric.] Gravity Probe B will attempt to

measure the force, gravitomagnetism, giving scientists an important insight

into how it might affect objects that are much larger than ping pong balls,

such as black holes. At the same time, the gyroscopes will experience a

much bigger force - the geodetic effect - which is a result of the warping

of space-time predicted by Einstein (see Diagram). This force will tend

to push their axes in a direction perpendicular to the frame-dragging effect

which allow it to be measured separately. The geodetic effect is hundreds

of times bigger than frame dragging and the experiment should measure its

size with an accuracy of 0.01 per cent the most severe test of general

relativity ever undertaken.

While the geodetic effect was first detected in 1988, gravitomagnetism has remained hidden because it is extremely weak. To get some idea of how weak it is, imagine that the axes of the spinning spheres are a kilometre long. In the course of a year, this force would move the ends of the axes by the width of a human hair, an angle of only 40 milliarcseconds. Gravity Probe B is designed to measure this effect with an accuracy of 1 per cent but it will be no easy task the slightest interference from unwanted forces will overwhelm the results." - B. Ianotta. Music of the Spheres. New Scientist, 31 August 1996, pp. 28-31.

One instance of gravitomagnetism has been detected by a team of astronomers using recent X-ray astronomy satellite observations. For more information, see the Marshall Space Flight Center space sciences feature article: "New Observations of Black Holes Confirm General Relativity."

Space-time is a four dimensional description of the universe that includes the usual three dimensions of height, width and length and a fourth dimension of time. You might be wondering how time can be considered a dimension and why it can be lumped in with space. Consider the definition of time: time as we know it is really a man-made concept and is defined by physicists to be the measurement of a series of events. If one considers what time really is, one can see that it is simply the counting or measuring of things occurring, such as the vibrations of a quartz crystal in a watch, or the movement of the earth around the sun. Really, time does not exist as its own entity; the event is the true variable we must consider when thinking about time. Without events occurring, there would not be a way to measure time. Now, getting back to our space and time link, an event must occur in a space. That point in space is particular to the observer (or measurer) of the event. Therefore each point in space is associated uniquely with an event. Thus space and time are tied intimately together. One can also see how the perception of events are "relative" to the observer depending on his vantage point. Hence the name "relativity" for this branch of physics.

One way to think about space-time is as a large fishing net. Left unperturbed and stretched out flat, it is straight and regular. But the minute one puts a weight into the net, everything bends to support that weight. A weight that was spinning would wreak even more havoc with the net, twisting it as it spun. The mass-energy of the planet earth represents a "weight" in our net of space-time, and the daily revolutions of the earth, according to Einstein's theory, represent a twisting of local space-time. GP-B will search for this twisting effect, which has never before been measured. Note that sometimes people ask for a three dimensional analysis instead. This can be difficult to visualize, but imagining space-time as a cube of Jello instead of a net seems to provide a decent analogy.

For a more technical definition of space-time, see a definition from the National Center for Supercomputing Multimedia Online Expo, "Science for the Millennium."

Einstein's equivalence principle postulates that there is no way of distinguishing locally between a gravitational field and an oppositely directed acceleration. This is a fundamental postulate to general relativity, tying mass and energy together. It has been partially verified by Gravity Probe A. For more information and understanding of the equivalence principle, check out "A Cultural History of Gravity and the Equivalence Principle."